Much has been said and written in the debate about risks and opportunities of a withdrawal from the European economic and monetary union (EMU), but in spite of intellectually consistent and rigorous contributions (by Alberto Bagnai and Luigi Zingales), useful to order and structure the discussion around the main issues, little has actually been added on the practical aspects of such a project.

Hal Scott’s article on “the unsolved issue of external debt” is one of the most useful contributions, because it clearly dissects one of the key issues to be sorted out when thinking about a unilateral withdrawal from a monetary union: the problem of redenomination of external debt for private contracts. He clarifies from a legal perspective the different implications in the case of public and private debt: the first could be easily redenominated because it is mainly issued under national law, while private obligations are often governed by another jurisdiction, therefore more difficult to redenominate.

The core of the problem, as Scott carefully mentions, is the case of a private contract between a domestic debtor and a foreign creditor: in this case, the redenomination would probably not apply to the contract, therefore, in the event of a depreciation of the domestic currency, the domestic firm would face an additional cost, having to repay the debt in euro while gaining its new revenues in a depreciated local currency. He concludes his legal analysis with the political consideration that “the leverage the EU would have over the terms of an Italian departure from the euro area would greatly exceed the leverage the EU now has on the terms of the U.K.’s departure from the EU itself”. This is probably meant to be so large to discourage an exit from the EMU.

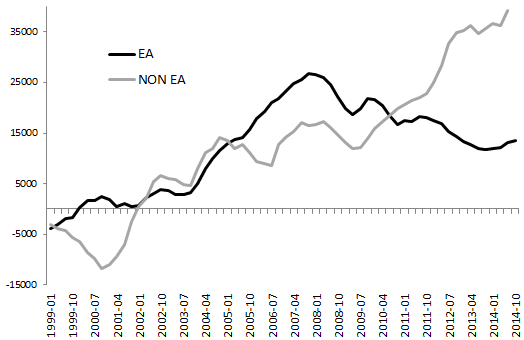

Let’s consider now the worst scenario, in which a redenomination of private debt is not possible. The case mentioned by Scott of a domestic firm with debt governed by a foreign jurisdiction, therefore unlikely to be redenominated in a weaker currency, is a very specific one, whose relative importance can be quantified. It is however the specular position of another equally possible case: a private contract between a domestic creditor and a foreign debtor. In such a specular case, the withdrawal from the monetary union with associated depreciation of the domestic currency would generate a net gain for the domestic firm, whose credit would be due in a stronger currency.

The effect of a withdrawal from the currency union on the balance sheets of domestic firms, therefore, is bi-directional: it can generate both new losses and gains. It is also important to consider that the size of the effects depends on the size of the expected depreciation (or appreciation) of the domestic currency vis-à-vis the euro.

One should consider the relative importance of the two specular situations of external debts and credits of domestic firms, in order to understand if and how they could offset each other. First of all, they could be partially offset at the level of individual firm; secondly, they could be partially offset by private insurance between net creditors and net debtors; but, finally, they could and probably should be offset by the government through a kind of general insurance contract, taxing the benefits emerged from the change of currency regime in the balance sheet of firms who are net creditors, in order to compensate those who are net debtor, for the incurred costs.

A perfect clearance of gains and losses through taxation and subsidies at national level might be difficult to achieve, but in the hypothesis that the maximum degree of offsetting would not be achieved, the resulting gains and losses could even trigger a selection process in the country by virtue of which firms with net external debts are substituted by ones with net external credits, which is likely to favour more productive firms over less productive ones.

This is the case of a unilateral withdrawal of one member state only, whose currency would depreciate vis-à-vis the euro. However, one should also consider the possibility that more than one country withdraw from the EMU: in that case, the balance of costs and benefits in private contracts arising from the exit should be assessed in all bilateral relations.

Let’s assume, for the sake of simplicity, that only two countries (A and B) leave the EMU, and that both of them see their currencies depreciate, by a different amount: A by 10%, and B by 20%. Private debtors in A would see their debt increase if it is with EMU creditors, but they would see it decrease if it is with B creditors. And vice versa: private creditors in A would gain if their debtors are in EMU and lose if they are in B. A comprehensive assessment of these costs and benefits, then, should calculate:

- the direction and the size of the movement in the exchange rate (appreciation or depreciation, by how much);

- the relative position of the new domestic currency vis-à-vis the euro and any other new currency;

- the aggregate bilateral balances between firms in the withdrawing country and those in the rest of the currency union, but also in each other withdrawing country.

The combination of these calculations will allow a proper cost-benefit analysis of the option to withdraw from the euro area and an assessment based on rational rather than emotional considerations.

In the case of Italy, recent estimates suggest that the depreciation of the new domestic currency would be minimal, compared with other potential “exiteers” (see for instance Durand and Villemont, 2016; or the current account and REER gaps calculated by the IMF, 2016; also here). This implies that the new Italian currency would not depreciate much vis-à-vis the euro, while if Italy’s withdrawal also triggered a withdrawal by other stressed countries, the new Italian currency would actually appreciate vis-à-vis their new currencies.

Finally, let’s not forget that here we have been analysing the extreme case of a unilateral and uncooperative withdrawal. Things would become much easier and more manageable if a cooperative process took place, in which for instance a common accounting unit would be created as reference, and a European Regulation would manage the new redenominations.

Agenor